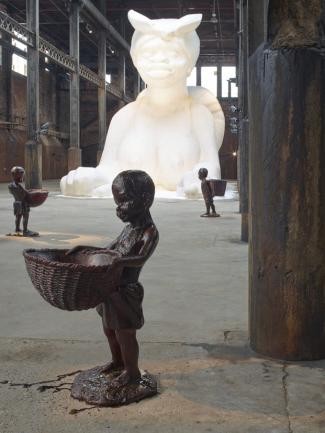

A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, artist Kara Walker's massive sculptural installation at the former Domino Sugar Refinery on the waterfront in Brooklyn's Williamsburg neighborhood, seems designed to put viewers into a state of unease. Commissioned by New York public art organization Creative Time, A Subtlety utilizes overtly racist imagery: a gigantic nude-as-sphinx, coated in sugar, recalls sexualized stereotypes of black women, with its exaggerated breasts and buttocks—the crouching figure's vulva is clearly visible from the rear—and recalls Aunt Jemima-style caretakers by way of its kerchief head wrap.

Furthering the discomfort are smaller, molasses-dark statues of boys holding baskets and loads of bananas, evoking the slave labor that fueled the sugar trade. Opened in 1882, the Williamsburg plant ceased operations only in 2004, and is now slated to give way to a $1.4-billion mixed-use complex, full of tech companies and high-rise condos, courtesy of Brooklyn real estate developer Two Trees Management. (Two Trees' head, Jed Walentas, is co-chairman of Creative Time's board.)

Much public response has been disheartening and callous. Social media sites like Instagram have abounded with images of visitors pretending to ogle, lick, probe and fondle the central sculpture. In hopes of remedying this reaction, a public gathering for people of color will take place at the refinery this Sunday. "The Kara Walker Experience: WE ARE HERE" is collectively organized by a number of New York artists and art lovers who are affiliated with neither Walker nor Creative Time. Participants are invited to wear all white; educational materials will be distributed.

Along with New York-based artist Salome Asega, the event's core organizers are Sable Elyse Smith, an artist and writer based in Brooklyn; New York musician, art producer and administrator Taja Cheek; Brooklyn's Nadia Williams; and Brooklyn artist Ariana Allensworth. The four discussed the project with A.i.A. via e-mail.

MATTHEW SHEN GOODMAN What was the impetus for this action?

SABLE ELYSE SMITH There is an absence of people of color accessing art spaces—specifically where the work addresses, in some form, a minority experience or identification. I have spent hours in the installation watching visitor after visitor fondle the sculpture for photo ops. Art instigates discourse, but someone has to initiate the dialogue. This work is too important for dialogue to not be incited.

NADIA WILLIAMS The first time I visited, there wasn't much press coverage yet, and seeing the space filled with an overwhelmingly white majority came as a shock. It was hard to avoid seeing small white children laughing at the artwork, smiling and posing for photos next to the figurines. The second time, I visited with my parents, and allowed myself to be hyper-aware of my surroundings. Seeing people giggle while taking photos of the sphinx's vagina—mostly white males—disgusted me. Seeing how deeply the sheer lack of respect impacted my mother was traumatizing. Reading Jamilah King's article "The Overwhelming Whiteness of Black Art" for [online news magazine] Colorlines really set me into action. She writes about the long history of exclusion of people of color from arts institutions. On the one hand, I was interested in creating this gathering as a space for people of color to experience the work in a healthier environment; on the other, it's an effort to do outreach to get our people to experience relevant art together.

SHEN GOODMAN Could Creative Time have better handled the public response?

SMITH The nature of Walker's work is to provoke. Viewers become complicit, repulsed and even seduced. I believe the work itself is functioning as it was intended to, and that may be the real subtlety of it all.

WILLIAMS I'm not sure it's productive to wonder what Creative Time could have done better. I recognize the limitations of an exhibition sponsored by the developer of the condos being built on the soon-to-be-demolished site. I wouldn't expect them to be excited to talk about gentrification, erasure of history, the impact the factory closing has had on the working-class community, or the exploitation of black and brown bodies in the sugar industry.

TAJA CHEEK My frustration that the exhibition failed to prompt critical engagement and create community is not morally driven; those failures are either aesthetic, curatorial, art historical or some permutation of the three. However, our identity as people of color informs how we are able to fill these voids and our sense of urgency while filling them. It also informs the swiftness with which we are able to sniff out disrespect and neglect: every Instagram photo and caption, every instance of someone licking the sugar off of the smaller sculptures' young black male bodies (yes, this actually happened several times); every fluffy article about the exhibition.

SHEN GOODMAN I'm also curious to hear your thoughts on the site, given that Williamsburg has been so drastically changed by gentrification.

ARIANA ALLENSWORTH I think it's critical for this exhibition, which claims to be site-specific, to honor the rich, complex, politicized history of the Domino site and Williamsburg at large. It's important to facilitate a space for visitors to reflect on their own positions in relation to the racial, gender and economic factors impacting the neighborhood.

For the past three years, I've been filming interviews with longtime Puerto Rican residents of South Williamsburg. A recurring theme is a collective sense of loss of what was once a thriving Latino community. The impending demolition of Domino is, in a lot of ways, symbolic of that loss. In the 1950s to 1980s, many members of the Puerto Rican diaspora found work at Domino and other since-outsourced manufacturers on the Williamsburg waterfront. After the Walker exhibition opening, I found myself in conversation with many folks about the exhibition's failure to address this context, though I was not surprised given the project's sponsors.

WILLIAMS The exhibition contributes to the erasure of history by reclaiming the Domino Factory as simply the site for the art show of the hour. It actually makes the erasure easier, because we're kind of talking about race and sugar, but we're not actually saying anything. So it seems like Two Trees is doing its part to make a community contribution, but it's actually just getting people excited so that when high rises are built there's this faint memory—but it's connected to something cool instead of a painful history.

SHEN GOODMAN What kind of outcomes, whether short or long term, would you like to see from Sunday's action?

SMITH I would love to see the gathering provoke more collective viewings and dialogues concerning art and cultural institutions. This event should act as a reminder that we have to create the spaces that we want and not expect them to be created for us.

WILLIAMS My main interest is to have people of color fill the space in order to experience the artwork and engage in a dialogue that feels safe, healthy and productive. I'd like there to be a range of people, including audiences who wouldn't normally go to a museum or a gallery. This moment is for us.

CHEEK This is an opportunity for people of color from all walks of life to meet, talk, organize, break bread and have fun. This action is a response to A Subtlety in particular, but our issues and frustrations with the art world at large are plentiful.