On April 4th, the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art joined institutions across the nation in celebrating artist Judy Chicago’s 75th birthday with a retrospective exhibit. Chicago in LA: Judy Chicago’s Early Work 1963-74 brings together over 55 pieces produced during the first decade of the feminist artist’s career, including well known works such as Rainbow Pickett (1965/2004), Birth Hood (1965/2011), and Heaven is for White Men Only (1973).

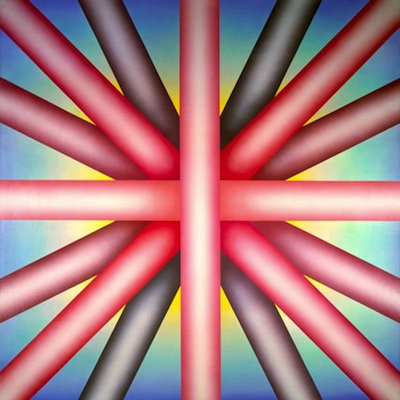

Though Chicago has at times expressed the relevance of content over form in her art, it is the striking interaction between the objects in her exhibit that helps draw the viewer into the significance of their content. The disparate mediums on display—which include large- and small scale sculpture, painting, china work, drawings, and an air-brushed car hood—are bridged by the cohesive palette of colors which characterize Chicago’s early works. This range in form pays testament to Chicago’s life-long dedication to master untraditional and varied techniques.

In addition to illuminating the breadth of Chicago’s craftsmanship, Chicago in LA tells a story of the transformation of the artist’s identity, politics, and self-awareness: it is the story of how she became the feminist artist she is today.

Chicago began her career at a time when, in her words, “you couldn’t be a woman and an artist too.” The earliest works on exhibit, made when she was a graduate student at UCLA, were criticized by her male peers and professors for evoking elements of the female experience. Her piece Mother Superette, for instance, was dismissed by her male professor on the basis of its “biomorphic breast and womb-like shape.” As a result of this resistance, Chicago recalls rejecting her impulses, thereby hoping to gain the acceptance of her male colleagues, whom she deeply respected.

Although she withheld from depicting explicitly female content, Chicago found ways to express her unique perspective through the use of repetition and color. Discussing her use of these techniques, Chicago notes, “I was trying to explore my own subject matter and still embed it in a form which would make it acceptable to the art world.” Thus, the bright tones emblematic of Chicago’s work, in addition to her experimentation with scale and repetition, can be seen as examples of the subtle resistance that she employed during this period.

However, the late ‘60s brought with them heightened visibility of second-wave feminism, and through increased exposure to radical literature and female activist communities, Chicago’s own viewpoint on her role as a female artist began to shift. Rather than suppress her impulses, Chicago let these impulses guide her as an activist and educator. She began to open up her imagery in sprawling paintings such as Silver Blue Fan (1971) and also engaged in large-scale, collaborative performance pieces. By the early ‘70s Chicago was actively using these pieces, as well as projects at Womanhouse (a feminist performance space that she co-founded) and collaborations with universities to develop more female-centric curriculum, to evoke the female experience as a vehicle for universality.

Curator Catherine Morris anticipates that the presence of Chicago’s early canon will help visitors recontextualize The Dinner Party, which is part of the Brooklyn Museum's permanent collection. The Dinner Party (1974-79), likely Chicago's most well-known work, is an installation piece commemorating 39 historically significant women through painted dinner plates. By literally bringing these women to the table, The Dinner Party seeks to address the erasure of women from Western Civilization's historical and cultural narratives. However, Morris does not want Chicago in LA to simply be framed as "the pieces that led up to The Dinner Party." Rather, she hopes that the retrospective collection will be understood as representing a meaningful body of work in and of itself, demonstrative of a highly prolific period of Chicago's career. Indeed, through the strength of the pieces on display, Chicago in LA effectively debunks the misconception that Chicago's career began with the success of The Dinner Party.

An issue to which Chicago often returns is the complicated relationship between progress and stagnation in societal attitudes towards women artists. On the one hand, it is clear that change has taken place in the five decades since she entered the art world. For the majority of her early career, Chicago couldn’t get any museums or galleries to show her work. Now, she is being honored in retrospectives and has pieces that are permanently housed in prestigious institutions. However, at a press review, Chicago was vocal about the prejudices that remain transparent today. Noting that the Museum of Modern Art will be dedicating 2015 to women artists, she states, “we get an exhibit? That was a strategy we used in the ‘70s! What we want now is 50 percent of the [museum’s permanent] space!” With world-renowned institutions like the MoMA still behind the times, it’s clear that the struggles depicted in Chicago’s early work regarding lack of female representation in the art world are still all too relevant.

Chicago in LA will be on exhibit through September 28, 2014. Chicago’s work is also currently showing in Mana Contemporary’s exhibit The Very Best of Judy Chicago, now through August 1.